UNESCO study: technical and vocational education

Field research for a UNESCO project took our Director Ben Gardiner and Researcher Ana Rosa Gonzalez-Martinez* to the Dominican Republic, Cyprus and Senegal to assess the potential for a training levy to support vocational and technical education.

Tell us about the UNESCO project

The project aimed to develop a methodology robust and flexible enough to estimate the amount of revenue from the private sector that could be mobilised by means of a training levy.

It was tested in three countries (Cyprus, the Dominican Republic and Senegal) that varied in terms of economic development and nature of the labour market.

What is a technical and vocational education and training (TVET) levy?

The levy is a way of providing funds for vocational education, which best meets the needs of employees who do not require a high level of formal education for the work they do.

This is especially the case in less-developed countries where employees often require on-the-job training to grow and develop in their roles.

However, it’s also relevant in western countries where hands-on learning is seen as essential to improving productivity growth. Simply increasing the supply of new graduates does not appear to be solving this puzzle.

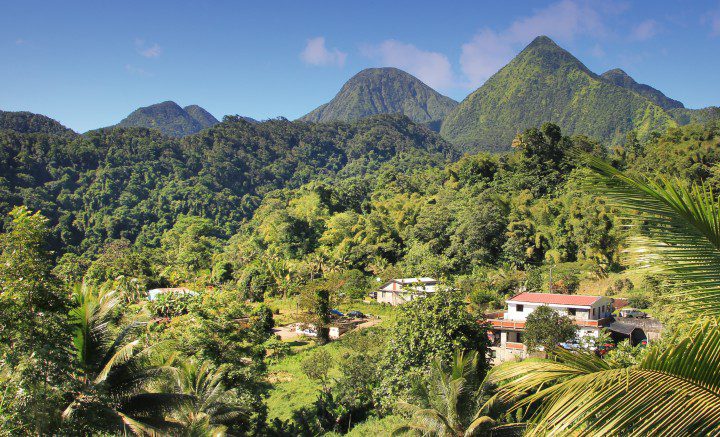

Countryside in the Dominican Republic

The international community’s vision for education is to ‘ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all’.

What contribution does research like this make to attaining this goal?

Firstly, the study raises awareness about the potential role that technical and vocational education can play in developing skills within the private sector. In the Dominican Republic, the report is being used as one of the main inputs for the development of a multi-stakeholder platform – aimed at improving the coordination of different actors in the labour market, from both the public and private sectors.

Secondly, at national level, we expect the study to help governments better understand the role of technical and vocational training. To do this they need to make their own estimations of the revenue that can be mobilised from the private sector for that purpose. This study can help them do that, in terms of building the technical capacity to develop their own forecasts.

Limassol, Cyprus

The research looked at the potential amount of revenue that could be raised through a training levy. Could you give us some figures to illustrate the findings?

For Senegal the results were quite extreme, because there was a fundamental shift in the way that training funds were being hypothecated from the tax base.

Previously only a small proportion (5%) of funds had been allocated to training, but an agreement was in place to increase this (to 100%, i.e. full allocation of funds) over a three-year period.

This in turn was expected to lead to a rapid increase in available training funds (from CFA 2bn in 2015 to CFA 29bn in 2018), something which raised questions over the ability of the current system to cope with and deal efficiently with the additional monies.

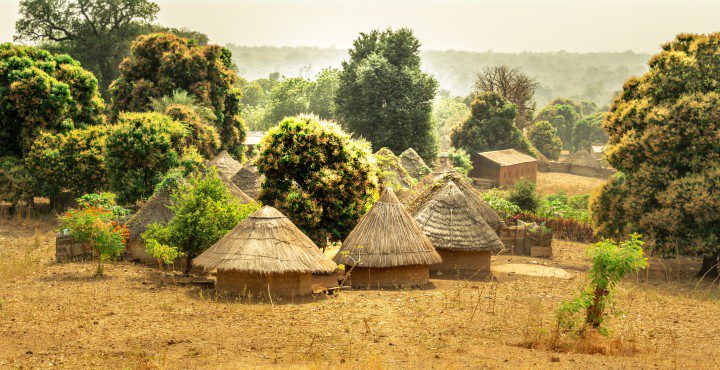

A traditional Bedik tribe bungalow in Senegal

The countries you visited as pilots were pretty diverse in terms of geography and demographics – tell us about this

The pilot study countries were chosen partly for the mix of geography but also because of the nature of their training schemes and funding mechanisms. Whilst there were great differences, there were also important similarities.

In all the cases we found that SMEs deserve special attention since they usually struggle to benefit from the system. For example, they find it difficult to allow their staff to attend training because they do not have additional capacity to cover for absent employees.

What did the pilot studies involve exactly?

Ben: The pilot studies typically involved a few days in each country, gathering background information on the particular TVET schemes, collecting data from government sources (which would have been difficult to obtain remotely) and talking with government officials and other stakeholders (e.g. trade unions or employers’ confederations) about how they viewed the TVET schemes as working.

It also looked forward to any future policy changes which might affect the TVET funding mechanism, which was important because the methodology used to forecast funds essentially relied on established historical relationships.

Ana: These visits left us with many (and unforgettable) anecdotes. For example, we interviewed several representatives of trade unions in the Dominican Republic.

One of them was based in a big district where the only business was the trade of tyres – mountains of tyres piling up everywhere!

Another interesting interview with a trade union representative happened in a less developed neighbourhood where people were extremely passionate about doing their work and helping deprived people to get out of the ‘poverty trap’. Their office was located in a semi-abandoned building and home to some unexpected neighbours – a bunch of chickens living in the rear garden!

What did you enjoy most about working on this report?

Ben: For me personally the trip to Senegal was both fun and challenging. Having to conduct the interviews in French and working with the local UNESCO office in Dakar presented a steep learning curve, but the experience of seeing the city and gaining first-hand knowledge from government officials was definitely a bonus.

Often project work can be desk-based and rely solely on secondary information sources – so it was nice to gain some first-hand experience!

Ana: The field visits were an enrichment since we managed to get a hint of the lifestyle in the pilot countries. The client was very happy with the outcome which is always a good reward. And most importantly, the cooperation between the different team members was excellent!

How will the report be used in future? What will its impact be?

The work has established a viable methodology through which TVET funds can be calculated.

It does require historical data series for existing TVET funds and also basic (macro) economic data, but other than that the principles that have been established could be applied by any country to improve on the way in which they forecast expected training funds.

This, in turn, can help government officials and training providers to improve allocation of training resources and thus delivery of services.

Where do we go to find out more?

The full report is available on UNESCO’s website.

Some of its content have been included in the ‘Handbook of Vocational Education and Training’.

*Ana Rosa Gonzalez-Martinez, formerly a Senior Economist at Cambridge Econometrics, now works at Wageningen University & Research (WUR).

For more information on the technical detail, please contact me.