Inflation – how worried should we be?

Senior Adviser Andrew Sentance argues that in terms of both monetary and fiscal policy, policy-makers in the UK and around the world need to take a gradualist approach to countering the current inflation surge.

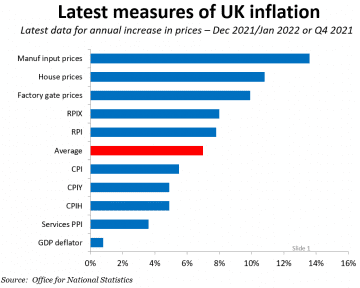

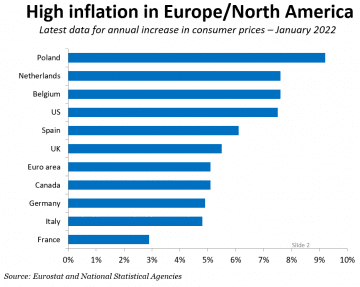

Inflation is on the rise in the UK and in many other countries around the world. Consumer Price Inflation has hit 5.5 percent in the UK, 5.1 percent in the euro area and 7.5 percent in the United States. The Bank of England’s latest Monetary Policy Report indicates that UK CPI inflation will also reach over 7 percent in the spring.

The scale of this inflation surge has taken policy-makers by surprise. Where is this rise in inflation coming from, and how long might it last?

It is driven by a mixture of global and domestic factors –some short-term but others threatening to be more persistent.

At the global level, the strength of the rise in demand – as lockdowns and other pandemic restrictions were eased – has put upward pressure on energy prices, other commodity prices and strained global supply chains.

In the case of the UK, manufacturing input prices were 13.6 percent up on a year ago January. The CBI’s Industrial Trends Survey has recently been showing the highest rates of cost and price increases recorded or expected since the 1970s and early 1980s.

These upward pressures on prices and costs from global markets will not subside quickly. The world economy is expected to grow strongly this year and next so global demand pressures are likely to continue to exert an upward influence on inflation for some time.

Meanwhile, the supply side of many economies is struggling to keep up with the bounce-back in economic activity we have seen since the first half of last year.

Tightness of labour markets

A major constraint on the supply side of the economy is the tightness of labour markets in many economies. Unemployment rates are at or close to historic lows in the US (4.0 percent), UK (4.1%) and Germany (3.2%) for example.

The lack of availability of labour is adding to wage pressures as skill shortages emerge in many industries.

In the UK, there are now nearly 1.3 million unfilled vacancies – compared to around 700-800,000 before the pandemic. The withdrawal of many workers from the labour force – sometimes described as “The Great Resignation” – has added to this problem as the supply of labour has fallen.

Labour shortages and resulting upward wage pressure could easily prolong the inflation surge as we look ahead. With productivity growth remaining sluggish, rising wages can only be accommodated by passing higher costs on to consumers in the form of higher prices.

The strength of the inflation surge creates dilemmas for both monetary and fiscal policy. Central Banks have been caught unawares and now face the challenge of rapidly reversing the stimulatory policies adopted in response to the pandemic.

However, Central Banks must strike a balance between the need to tighten policy in response to the threat of inflation and the risk of destabilising the growth path of the economy.

Gradual interest rate rises and cautious approach to unwinding QE

Gradual interest rate rises and a cautious approach to unwinding QE still seem the best course of action.

Market expectations are for the UK Bank Rate to reach 1.5 percent by mid-2023 – and further interest rate rises will probably be needed as we move through the mid-2020s.

By consistently and gradually raising interest rates – and communicating this policy clearly to the public and the markets – the Bank of England will be signalling that it is committed to heading off a longer and more sustained surge in inflation.

What about fiscal policy?

On the fiscal policy front, the dilemma is between the objective of moving the public sector deficit to a more sustainable position and taking steps to ease the cost of living squeeze – particularly on poorer households.

The UK government, however, has got itself into a muddle in terms of its fiscal strategy. It is sticking to its plan to raise National Insurance rates in April, which will add to business costs and add to the burden on the lowest paid (remembering that National Insurance is paid by employees and the self-employed at much lower earnings than income tax). At the same time, a package of measures has been announced which aims to give fiscal support to reduce energy bills.

Apart from the fact that the Chancellor Rishi Sunak appears to be giving with one hand and taking away with another, the energy price support package is not well targeted. It is a combination of a reduction in energy bills for all consumers which has to be paid back in future years and a Council Tax reduction.

Council Tax, however, is still based on early 1990s property values, and is a very poor mechanism to help households with their energy bills.

While there needs to be a long-term plan to bring government borrowing down gradually, there is no urgency about the timing of this reduction.

The UK government is still borrowing very easily on bond markets at low rates of interest. If – as seems likely – global interest rates rise through the 2020s, it will then become more important to take more concrete steps to reduce the public deficit.

Even then the objective should be to achieve a more modest level of public borrowing (eg 2-3 percent of GDP). There is no need to target budget surpluses or aggressive debt reduction.

Sensible controls on public spending will help with the process of deficit reduction. And on the revenue side we need a programme of long-term tax reform aimed at generating extra revenue by dealing with anomalies and distortions in the tax system.

A long-term fiscal programme of deficit reduction and tax reform can safely be implemented over a number of years (eg 5 years or longer). More immediate short-term tax-raising measures which will aggravate cost pressures and squeeze consumers further – like the planned rises in National Insurance – should be postponed or implemented much more gradually.

In terms of both monetary and fiscal policy, policy-makers in the UK and around the world need to take a gradualist approach to countering the current inflation surge.

That would be better than the alternatives of a kneejerk aggressive tightening of policy – which could trigger a recession – or neglecting the rise in inflation, and then having to take much more dramatic policy action later this decade.

Sign up to our newsletter for our latest news, opinions and collaborations from around the world.