Spring Statement: The curious case of the UK’s tight labour market

Ahead of the UK’s Spring budget statement, Senior Adviser Andrew Sentance delves deeper in to the drivers behind UK’s tight labour market. How is the UK’s sluggish productivity having an impact and what are the drivers behind workers leaving the labour market? Key issues, Andrew argues, that must be addressed by the Chancellor Jeremy Hunt to ‘get Britain back to work’.

Over the past 3 years – which has been dominated by the pandemic and successive lockdowns – one thing has been surprising: the resilience of the UK labour market.

Normally, recessions create a serious amount of labour market disruption. After the early 1980s recession, it took over two decades before unemployment levels returned to the late 1970s norms. There were serious problems of labour market “hysteresis” through the 1980s and 1990s – mainly associated with long-term unemployment.

The UK labour market is not necessarily performing normally, however. It is not showing a classic post-recession pattern of behaviour. In fact, the UK labour market is still very tight – with high levels of vacancies, low unemployment and accelerating wage inflation. Pay increases in the private sector are currently running at 7.3 percent – totally out of kilter with the 3-4 percent wage inflation which might be consistent with 2 percent price inflation.

Why is that, and what should policy-makers be doing to address the tight UK labour market situation?

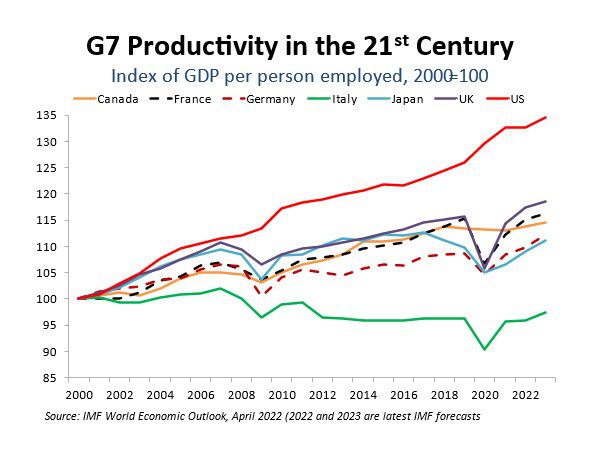

This is not an isolated issue facing the UK. Across the G7 economies, most unemployment rates are at historic lows and the average G7 unemployment rate is currently 4 percent – well below its average since 1980 (6.3 percent). Low unemployment and other labour market pressures are at risk of fuelling a more general wage-price spiral across the western world.

It helps to run through the facts. Despite the traumas of the pandemic and lockdowns, UK employment levels have returned very close to pre-pandemic levels. At the end of 2019, there were about 32.9 million people employed in the UK. The latest ONS figures report 32.8 million employed. Given that GDP has been on a massive roller-coaster over this period (eg GDP falling by about a quarter in the spring/summer of 2020) and is only just getting back to its pre-pandemic level, that is quite a good outcome.

But even more puzzling still is the high level of job vacancies. Before the pandemic, UK job vacancies were around 800,000. The number of reported vacancies peaked at just below 1.3 million in mid-2022, ie roughly half a million above the pre-pandemic level. Since then, vacancy levels have dropped back, but are still close to 1.15 million.

If you add together reported vacancies and current employment levels, the demand for labour now seems to be higher after the pandemic than it was in 2018/19. What’s causing this?

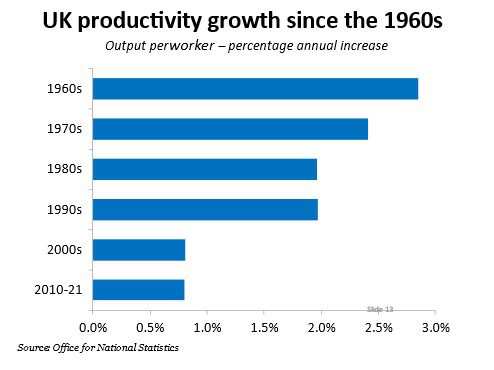

1. Sluggish productivity growth

This is a long-term issue which seems to have been with us since the start of the 21st century. We normally used to rely on UK productivity growth of about 2 percent per annum. But in the past 2 decades, the UK has achieved just 0.8 percent per annum productivity increases. Many other western economies have suffered a similar productivity slowdown.

2. Contraction in Labour Supply

This is most clearly evident in the numbers of people who are “economically inactive” – neither working or looking for work. In the 16-64 age bracket, there are now 8.9 million economically inactive people. That is a rise of around 400,000 since before the pandemic. If we look more broadly, and include older workers, the rise in economic inactivity is 650,000. In relation to the current size of our workforce, this is a very sizeable drop – around 2 percent.

What is driving this withdrawal of workers from the labour force? In the United States, it is described as the “Great Resignation” – but this is too simplistic a view.

Key drivers of workers leaving the labour force

- Long term-health problems: either directly due to the pandemic (long Covid) or because of untreated health problems (especially cancer) when health resources were skewed so heavily towards Covid in the period 2020-22.

- Lifestyle choices have favoured early retirement: a big source of employment growth before the pandemic was people in their 60s and 70s continuing to work. But this has now come to a juddering halt and gone into reversed. For high paid workers, one of the reasons for this may be tightening the limits on ”pension pot” income. Why try and earn more money when you are going to eventually pay more tax on your pension pot?

- Impact of the pandemic itself on the way in which people engage with the labour market: Working from home, furlough, disrupted employment history, etc may have persuaded many people that being outside the labour market is a better option than regular work.

It is hard to allocate responsibility to these various influences on UK labour market behaviour. But the Chancellor Jeremy Hunt has an opportunity to address these issues in his forthcoming Budget, and help “get Britain back to work”. Let’s hope he rises to the challenge.

Sign up to our global newsletter for the latest news, expert commentary and insights from around the world.